Looking through some graduate work the other day I came across a reference to “the Queen’s English,” in scare quotes, used in the general sense to describe the phenomenon of socially privileged dialect (as opposed to a specific British class dialect).

I’ve never heard “the Queen’s English” actually referred to positively or unironically. In my experience it has only ever been used to critique social (or imperial) privilege. As Ali G told an enthusiastic Sally Jesse Raphael studio audience:

I tell you there’s a lot of people who is livin’ not like da Queen who don’t speak like da Queen. So it ain’t my problem if I don’t sound like da Queen. I ain’t da Queen. Once they start putting a crown on ma head, givin me all da money, then maybe I’ll start speakin’ like da Queen. Till that time I ain’t speakin’ like da Queen. [Da Ali G Show, 14.04.2000]

As it turned out, though Ali G didn’t sound like da Queen (let alone any other UK accent I’ve heard), on occasion da Queen Mum was wont to sound like Ali G: “Standing in the dining room at Sandringham, she turned to the Queen, snapped her fingers Ali G-style and said: ‘Respec’.” [“Grandma did Impression of Ali G” Daily Mail, April 2002]. Social and cultural authority are always more complex than they may first appear, and prejudice of both kinds can be multidirectional.

Anyway, so I started to wonder about the history of the phrase, which I vaguely associated with Shakespeare. OED has a definition under queen, n.:

Queen’s English n. (usu. with the) the English language regarded as under the guardianship of the Queen of England; (hence) standard or correct English, usually as written and spoken by educated people in Britain; cf. King’s English n.

1592 T. Nashe Strange Newes sig. B1v, He must be running on the letter, and abusing the Queenes English without pittie or mercie.

a1753 P. Drake Mem. (1755) II. iii. 81 He was pretty far overcome by the Champaign, for he clipped the Queen’s English.

Of course such a term would first be recorded in a fit of language peevery–in this case part of a long attack on Nashe’s pamphleteering antagonist, Gabriel Harvey. While there are one or two positive, unironic invocations of King’s and Queen’s English in the OED record, this linguistic standard is almost always part of some kind of censure. Whether you approve of the Queen’s English or not, it seems, you’re most likely to invoke the idea in order to disapprove of someone else’s way of talking (be it QE or not QE).

“Abusing” and “clipping” are two of the most common things one can do to the Queen’s English. And to the King’s, according to the first two recorded uses in OED (s.v. king):

a1616 Shakespeare Merry Wives of Windsor (1623) i. iv. 5 Abusing of Gods patience, and the Kings English.

1737 B. Franklin Drinker’s Dict. 13 Jan. in Papers (1960) II. 176 A Man is drunk… Clips the King’s English.

Franklin is recording euphemisms for drunkenness, so apparently Sir Peter Drake’s 1753 usage of “the [monarch]’s English” was already common enough in the American colonies in 1737 to be included, albeit in the masculine form.

Now, when Nashe wrote of the Queen’s English, the reigning monarch was Queen Elizabeth I. Though Shakespeare probably wrote Merry Wives of Windsor during her reign, when the play was first published in 1602, the monarch was King James I.

Does this explain the shift in royal gender? The Times (London) maintains a digital archive from 1785 to 2008. In those 223 years, there were two female sovereigns of England, ruling (if you can call Elizabeth II a “ruler”) for a combined 120 years, or 53% of the time span. We can see in the following table that in the pages of The Times, you are much more likely to find reference reference to a male monarch’s English when a male monarch is on the throne, and vice versa:

[ws_table id=”5″]

However, there may be more to the story. It’s rather striking that in the period between Victoria and Elizabeth II, there are virtually no mentions of “the Queen’s English” in The Times. In fact, of the three hits, one is not relevant (“the Queen’s English origin…”) and the others are from May and September ’52, after ERII became sovereign. This, compared a persistence of “King’s English” in the periods when a Queen reigned (“Queen” yet enjoying a healthy enough ratio of 6 “Queens” to 1 “King” in both periods).

Looking at the Google Books corpus, we see a somewhat different picture, with a sharp spike and drop in “Queen’s English” during the middle of the Victorian period: [click graph to embiggen]

The rise in “King’s English” actually begins around the same time-1860 or so–and continues gradually until 1952, when it begins to taper off. Despite the steady decline, “King” continues to outnumber “Queen” right up to the end of the century. In fact in Google corpus “King” beats “Queen” in all years, except 1859-1903.

The rise in “King’s English” actually begins around the same time-1860 or so–and continues gradually until 1952, when it begins to taper off. Despite the steady decline, “King” continues to outnumber “Queen” right up to the end of the century. In fact in Google corpus “King” beats “Queen” in all years, except 1859-1903.

So what happened in the early 1860s, to make “The Queen’s English” shoot up in this corpus? It may have to do with a popular and controversial manual of usage and style, published in 1863 by Henry Alford, Dean of Canterbury, a theologian, visual artist, hymn-writer, translator, and poet. A Plea for the Queen’s English: Stray Notes on Speaking and Spelling begins with a rather well considered elaboration of the idiom:

The Queen (God bless her!) is, of course, no more the proprietor of the English language than any one of us. Nor does she, nor do the Lords and Commons in Parliament assembled, possess one particle of right to make or unmake a word in the language. But we use the phrase in another sense … We speak of the Queen’s Highway, not meaning that Her Majesty is possessed of that portion of road, but that it is the high road of the land, as distinguished from by-roads and private roads: open to all of common right, and the general property of our country. And so it is with the Queen’s English. It is, so to speak, this land’s great highway of thought and speech…

I like that, even if I doubt Alford’s lengthy consideration of “upon” vs. “on to” or “as” vs. “so” in comparatives helps clear the highway of any real hazards. This metaphor, at least, gets us away from the idea of a particular person’s speech setting a national standard, and also from the body politic metaphor.

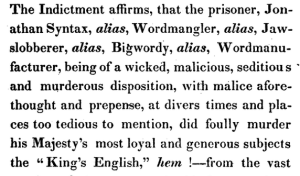

Which is not to say it isn’t open a certain line of parody, as in this American pamphlet from a few decades earlier.

Which is not to say it isn’t open a certain line of parody, as in this American pamphlet from a few decades earlier.

Alford’s book went through several editions, in England and in America, where a reviewer was “repelled…by a violent ebullion of spite against his native country” and found “that our author is somewhat under the dominion of class and national prejudices.” [North American Review, Oct. 1866]

A second reason for the high rate of occurrence of the term is George Washington Moon (1823-1909), who, shortly after Alford, published The Dean’s English: A Criticism of the Dean of Canterbury’s Essays on the Queen’s English (1864), which gave the opinion that the author of the former, having “actually assumed the office of public lecturer on the Queen’s English” was “so ignorant of its simplest rules, that the grossness of his errors in grammar and composition, even in his lectures, made him the laughing stock of those whom he thought himself competent to instruct.” Moon was famous for this sort of counter-peeving attack. He later authored The Bad English of Lindley Murray and other Writers on the English Language, a Series of Criticisms (1868).

So with all this back-and-forth in the 1860s, with several editions of both books containing dozens or hundreds of mentions of “the Queen’s English”, plus an assortment of reviews and assessments of Alford, Moon and their feud, the phrase enjoys a sharp increase in frequency.

There is more, however, to the persistence of “King’s English” in times of female reign. When Moon set out to write his own usage manual, in 1881, he called it The King’s English. As England still had a Queen, Moon explained the title this way:

‘The King’s English,’ is a name which our language has borne for centuries. The Rev. Richard Morris, LL.D., quotes in his ‘Historical English Grammar,’ a passage from a work by Thomas Wilson, which shows that in 1553* the expression was in common use; and, unless that work was published in the first half of that year, it really was issued when there was, as now, a Queen on the English throne.

My object in choosing the name as a title for this book, is merely to distinguish it from a work written by my worthy antagonist, the late Dean Alford, and entitled, ‘The Queen’s English’.

For a specimen of real ‘Queen’s English,’ take the following which was found written in the second Queen Mary’s Bible:–“This book was given the King and I at our crownation.”

I’m not sure how to take that last dig–I’d like to think it’s a general warning against class-based grammar advice, but that kind of wisdom is probably not to be found in the preface to a book on the King’s English. More likely it’s just garden variety misogyny (albeit surprising with Victoria on the throne) associating correctness of expression and style with other forms of manliness.

Other usage manuals which invoke and defend “the [sovereign]’s English” as a standard of correctness include: Bygott and Jones’s The King’s English and How to Write it [1904]; Fowler and Fowler’s The King’s English [1906] (one of them that Fowler); Williams and Smith’s The “King’s English” Dictionary [1920]; Clarke’s The spelling of the King’s English [1921]; Weston’s Using the king’s English, some guidance to practice [1938]; Turner and Ellis’s For English undefiled; in defence of the Queen’s English [1953]; Wall’s The Queen’s English : a commentary for New Zealand [1958]; Wolley’s The Queen’s English : exercises in the pronunciation of English [1974]; and Kingsley Amis’s posthumous peeve-pot The King’s English [1997]. Now, lest you fault Amis for a lack of gender correctness, remember he himself was sometimes called “Kingers,” “King,” or “The King.”

*[Odd that OED1 should have missed Wilson’s talk of “counterfeiting the king’s English” — it antedates the Shakespeare by almost 50 years, and appears to have been generally known among linguists and grammarians in the latter half of the 19thC. ]

reminds me of when I first heard the title “The King’s Speech” and thought for a brief moment it was going to be a Derridean film about royal nominal identity and ways of speaking.

not about Colin Firth bumbling his way through one specific speech. ugh

Love the Scatter & Squabble image

Murder!!? “Jawslobberer” is pretty good. “Wordmanufacturer” lacks bite.